Children of Deaf adults (Codas) grow up between worlds just as traditional Third Culture Kids do. A FIGT Research Affiliate webinar on 24 July explored how, with Erin Mellett and Alexander Laferrière.

.png)

The FIGT Research Network (FRN) Affiliate held an online seminar on 24 July 2020 with Erin Mellett and Alexander Laferrière to discuss the similarities between hearing children of Deaf adults (Codas) and traditional, internationally-mobile Third Culture Kids (TCKs), and to examine how the Coda experience might expand and enrich our understanding of the “third culture.” Sarah Gonzales, Co-Chair of the FIGT Research Network, hosted the event.

[NB: In general, “deaf” refers to the biological condition of not hearing while “Deaf” refers to a group of deaf people who share a culture. Please visit the link in Resources for more on this.]

Codas and TCKs: Growing up among worlds

Erin, a PhD candidate in anthropology, began by explaining that Codas—born to and raised by Deaf parents—grow up in the Deaf world, yet their ability to hear puts them in a unique position between the hearing and Deaf worlds. Through her 2016 master’s project at Boston University, Erin sought to understand Codas as inhabitants of both (or neither) the Deaf and hearing worlds (see Resources for a link to her thesis).

Despite being biological relatives of Deaf people and being raised by them, Codas lack the biological feature (deafness) necessary to be considered completely part of the Deaf community. At the same time, Codas don’t feel as though they belong to the hearing world either—citing distinctly “Deaf” ways of being that don’t mesh with hearing culture.

Robert Hoffmeister, professor of Deaf Studies at Boston University and himself a Coda, explains in Open Your Eyes: Deaf Studies Talking (2007):

...all Codas grow up in two worlds, the Deaf world of their families and the Hearing world. Every Coda leads two lives: one as Codas and one as a hearing person. They may choose to only live one life, but all of them have two.

Like traditional TCKs, Codas spend their childhoods “growing up among worlds.”

In fact, it was Erin’s Coda research participants who introduced her to the concept of TCKs and who told her that they felt a sense of affinity to people like TCKs.

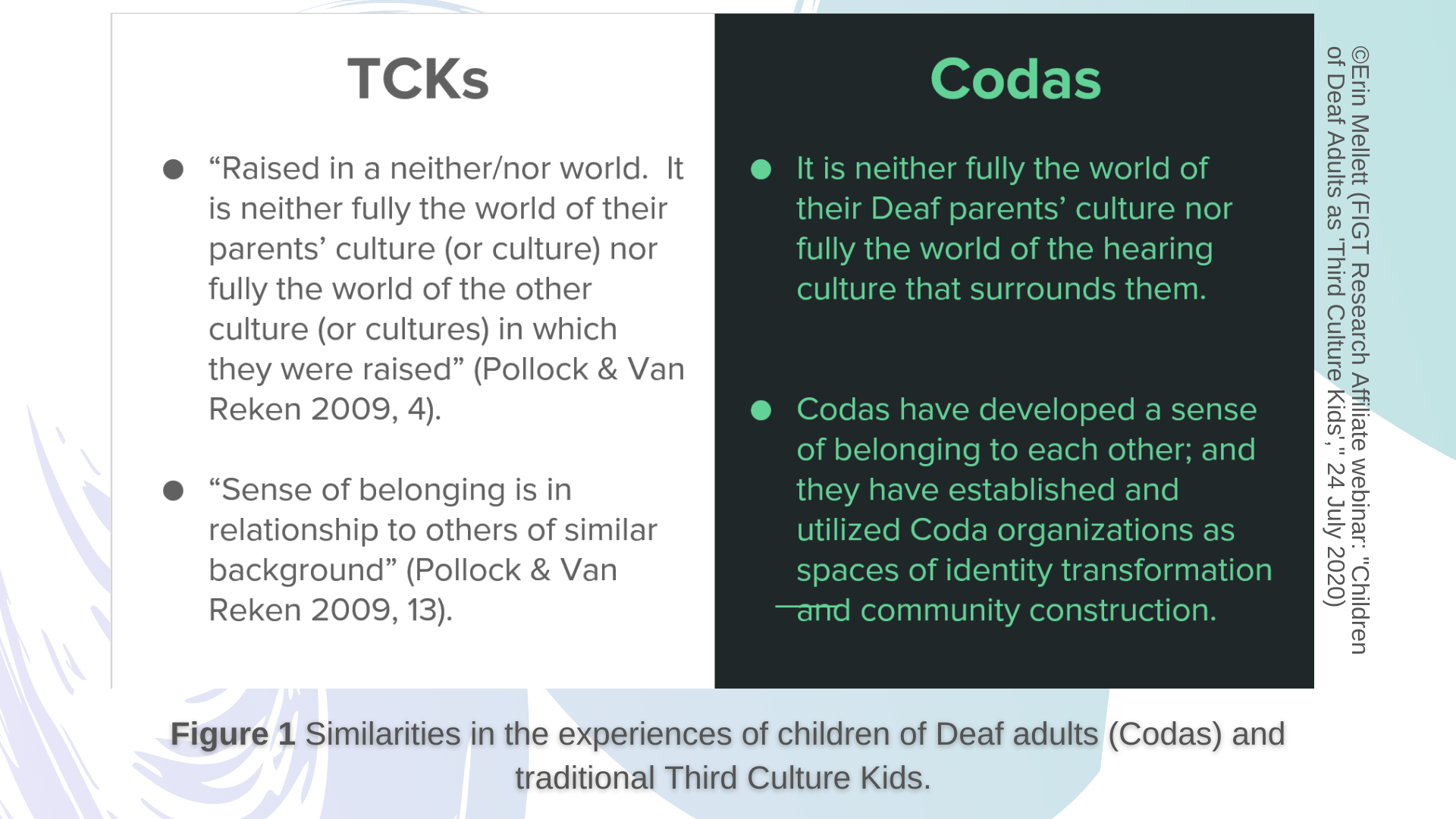

Both Codas and traditional TCKs have connections to multiple cultures while not fully claiming membership in any. Codas don’t fully belong to their Deaf parents’ culture nor the hearing culture that surrounds them.

Both feel a sense of belonging with others who share a similar background. For example, Codas have built a community through organizations like CODA International, where they have the space to explore their identities.

Codas can be considered a type of cross-cultural kid (CCK), like children of immigrants or international adoptees, who don’t fit the classic definition of internationally-mobile TCKs.

Both Codas and traditional TCKs have connections to multiple cultures while not fully claiming membership in any.

However, inspired by FRN’s seminar series (in particular, FRN Co-Chair Danau Tanu’s provocations), Erin suggested that instead of trying to determine whether or not Codas are TCKs or CCKs, it may be more useful to look at the third culture (or interstitial culture) as an analytical concept and to ask: how might Codas’ experience of the third culture be unique?

Erin explained that for Codas, biology (i.e., whether one can hear or not) is integrally linked to cultural affiliation (i.e., Deaf versus hearing). As biological relatives, but not biologically deaf themselves, Codas do not feel as though they can truly claim their parents’ culture—no matter how intimately they know its language and customs.

This means that the space of the third culture—the community Codas create with each other—becomes even more important as Codas try to establish their sense of belonging.

One Coda’s “me-search”

Following Erin’s talk, Alexander Laferrière—a Coda—shared his experiences with CODA International and coming to understand his own identity as Coda.

Finding this Coda identity helped him recognize that “there is value to my experience”

Alex comes from a large Deaf family that includes parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles who are Deaf; he grew up with sign language as his home language. But Alex didn’t realize that his experiences had a name until he was introduced as an adult—purely by chance—to the term “Coda.”

Finding this Coda identity helped him recognize that “there is value to my experience and if I could channel it or pursue it, it would be valuable for our community.”

Now, he tells stories through film to define, refine, and spotlight the Coda culture. He is also passionate about promoting broader awareness and acceptance of sign language as an important medium for communication.

As part of his “me-search,” Alex created a film asking other Codas what CODA International conferences mean to them (see the film under References). The way Codas describe CODA International conferences are strikingly similar to how traditional TCKs describe meeting each other in FIGT conferences.

Other perspectives from the floor

During the discussion session, Oya Ataman, a multilingual sign language interpreter, shared her perspective as a German Coda of Turkish descent. Oya was the first to alert Dr Ruth Van Reken about the need to include the experiences of Coda in Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds and is featured in the 3rd edition of the book.

Oya urged us to take more time to consider the vast similarities between Codas and expat TCKs, immigrant children, and so on, to avoid the trap of feeling “terminally unique,” a sense of feeling that one is “so different no one else in the world can understand them” (from Third Culture Kids, 3rd ed.).

She suggested that the experiences of Codas from culturally or ethnically diverse backgrounds may shed more light on the ways in which Codas are similar to other groups that experience that interstitial, third culture in childhood.

Marilyn Gardner, a public health nurse and writer, asked a question that further highlighted the intersectionality of many of these third culture experiences. A Russian family known to Marilyn immigrated to the US several years ago. She asks: “The parents are deaf and the children are hearing, but the parents only understand Russian and Russian sign language. The children end up being their primary interpreters in social settings—how can we support them?”

Clearly, there is more that we need to learn about new ways of living in the third culture.

* Our thanks to Erin Mellett for funding the American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters for the seminar and to the Rhode Island Commission for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (RICDHH) for providing the interpreters.

Resources

References

Hoffmeister, Robert. 2008. “Border Crossings by Hearing Children of Deaf Parents: The Lost History of Codas” In Open Your Eyes: Deaf Studies Talking, edited by H-Dirksen L. Bauman, 189-215. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Mellet, Erin. 2016. “Cochlear implants and codas: the impact of a technology on a community,” Boston University School of Medicine.

Pollock, David C. and Ruth E. Van Reken. 2009. Third Culture Kids: The Experiences of Growing up among Worlds. Boston, MA: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Preston, Paul. 1994. Mother Father Deaf: Living Between Sound and Silence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Preston, Paul. 1995. “Mother Father Deaf: The Heritage of Difference.” Social Science Med 40(11): 1461-1467.

Preston, Paul. 1996. “Chameleon voices: Interpreting for deaf parents.” Social Science and Medicine 42(12): 1681–1690.

Bios

Erin Mellett, MS, is a PhD candidate in the Anthropology department at Brown University. She obtained a Master of Science in Medical Anthropology from Boston University School of Medicine in 2016. Erin's research interests include Deafness and the Deaf community, disability studies, language, and belonging. Erin's current and ongoing dissertation research with deaf immigrants in the United States sits at the intersection of a number of fields including medical anthropology, Deaf studies, disability studies, linguistic anthropology, and immigration studies.

Erin Mellett, MS, is a PhD candidate in the Anthropology department at Brown University. She obtained a Master of Science in Medical Anthropology from Boston University School of Medicine in 2016. Erin's research interests include Deafness and the Deaf community, disability studies, language, and belonging. Erin's current and ongoing dissertation research with deaf immigrants in the United States sits at the intersection of a number of fields including medical anthropology, Deaf studies, disability studies, linguistic anthropology, and immigration studies.

Alexander Laferrière, MPA, is a third-generation American Sign Language user within a large Deaf family. Alexander’s background and passion have led him to work professionally with the global Deaf community in the intersection between government, policy, and media through CODA International. His expertise in interactive media, coupled with his master’s studies in Public Affairs has allowed him to create films and policy recommendations for various communities around the world, from Providence, Rhode Island, to Moyobamba, Peru.

Alexander Laferrière, MPA, is a third-generation American Sign Language user within a large Deaf family. Alexander’s background and passion have led him to work professionally with the global Deaf community in the intersection between government, policy, and media through CODA International. His expertise in interactive media, coupled with his master’s studies in Public Affairs has allowed him to create films and policy recommendations for various communities around the world, from Providence, Rhode Island, to Moyobamba, Peru.

Sarah Gonzales is Director of Graduate Programs at the University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV) School of Law. She also serves at NAFSA: Association for International Educators, teaching Intercultural Communication in Practice, Admissions and Placement of International Students, and Assessment and Evaluation for International Educators. Sarah is currently pursuing doctoral research on the intersection of cultural intelligence and mediation skills of TCKs. She is Co-Chair of the FIGT Research Network.

Sarah Gonzales is Director of Graduate Programs at the University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV) School of Law. She also serves at NAFSA: Association for International Educators, teaching Intercultural Communication in Practice, Admissions and Placement of International Students, and Assessment and Evaluation for International Educators. Sarah is currently pursuing doctoral research on the intersection of cultural intelligence and mediation skills of TCKs. She is Co-Chair of the FIGT Research Network.

[Edited by Danau Tanu and Ema Naito]